Investing in U.S. stocks had few bigger fans than the late, great Jack Bogle.

“If you hold the stock market, you will grow with America,” the legendary Vanguard founder told CNBC in 2018, less than a year before his death.

He famously suggested keeping things simple. Invest through low-cost index funds (such as Vanguard’s), he said. Don’t get too clever by trying to “time” the market, hoping to beat the big swings, he warned. And just stick to U.S. stocks, he advised. He saw no particular reason to invest internationally.

So what would he make of today’s highflying stock market, where the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA,

I’d hazard to say: He wouldn’t be a big fan.

I’d bet he’d be warning investors to take a second or third look at the risks they’re taking in their retirement accounts—where, according to Vanguard’s own data, about two-thirds of the average portfolio is being gambled just on U.S. stocks.

And, most intriguing, I wonder if he’d change the habit of a lifetime and be willing to bet big on overseas markets instead of just the U.S., as recently recommended by the company he founded.

I’m not saying this because I’ve been back to Salem, Mass., to consult witch-doctors or commune with the dead. Bogle died in January 2019.

But we don’t have to guess what he would have thought about U.S. valuations because he gave us a pretty good idea.

Two years before he died, in 2017, Bogle warned that U.S. stocks were already so expensive that longer-term, 10-year returns on a broad stock market index fund were likely to be meager at best.

His forecast: About 4% a year.

That, he said, was based on three things that anyone could calculate and which had an excellent long-term track record of predicting returns. He started with the dividend yield on the broad U.S. market at the time, which was around 2%. He added growth in corporate earnings, which were likely to average around 4 or 5% a year. And then he subtracted a percentage point or two a year, because he expected price-to-earnings levels on the market to decline back towards their long term average.

That was in March 2017.

But here’s the problem. Since then, U.S. stocks have already produced all of the returns he predicted for the next 10 years—and then some.

Bogle’s forecasts implied that the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund VTSMX,

But it’s already risen 70% — with six years to go. Not to put too fine a point on it, but to hit Bogle’s forecasts it would have to lose more than 2% a year through 2027.

Meanwhile the numbers Bogle used to build his forecasts look even worse than they did then. The dividend yield on the S&P 500 SPX,

Corporate earnings are going to be hard pressed to rise more than 5% a year when the Congressional Budget Office is predicting total gross domestic product to rise by less than 4% a year, on average, over the next decade.

Oh, and the forecast price-to-earnings ratio on the S&P 500, which was 18 when Bogle gave his interview, is now about a fifth higher at 22 times.

All of which means the risks are higher than they were four years ago and the likely outcome worse.

There are important caveats. Bogle warned several times last decade about the risks of rising U.S. stock valuations and the likely effect on long-term returns. His warnings were either wrong or at least premature. So you can figure the same applies today.

All forecasts are subject to massive amounts of error. They’re guesses, even if they are based on math.

On the other hand, rising U.S. stock valuations pose a major potential risk to Americans’ retirement plans. They may actually pose the biggest single risk, because U.S. stocks dominate the average 401(k) and individual retirement account so much.

Which brings us to a major alternative to U.S. stocks in your 401(k): International stocks.

We’re talking about developed markets like Europe, Japan and Australia, rather than the more volatile “emerging markets.”

“We expect higher international equity returns over the next decade compared with the last, and we believe that U.S. equity returns will be about 8 percentage points lower than the last decade on an annualized basis,” write Vanguard strategists in a recent note.

They calculate that over the next 10 years, U.S. stocks are likely to gain around 4.7% a year on average, which works out at a total gain over a decade of around 60%.

International stocks? They expect an average of just over 8% a year. That would work out at a total gain over the decade of about 120%, or twice what you would get on U.S. stocks.

All the same caveats about forecasts apply.

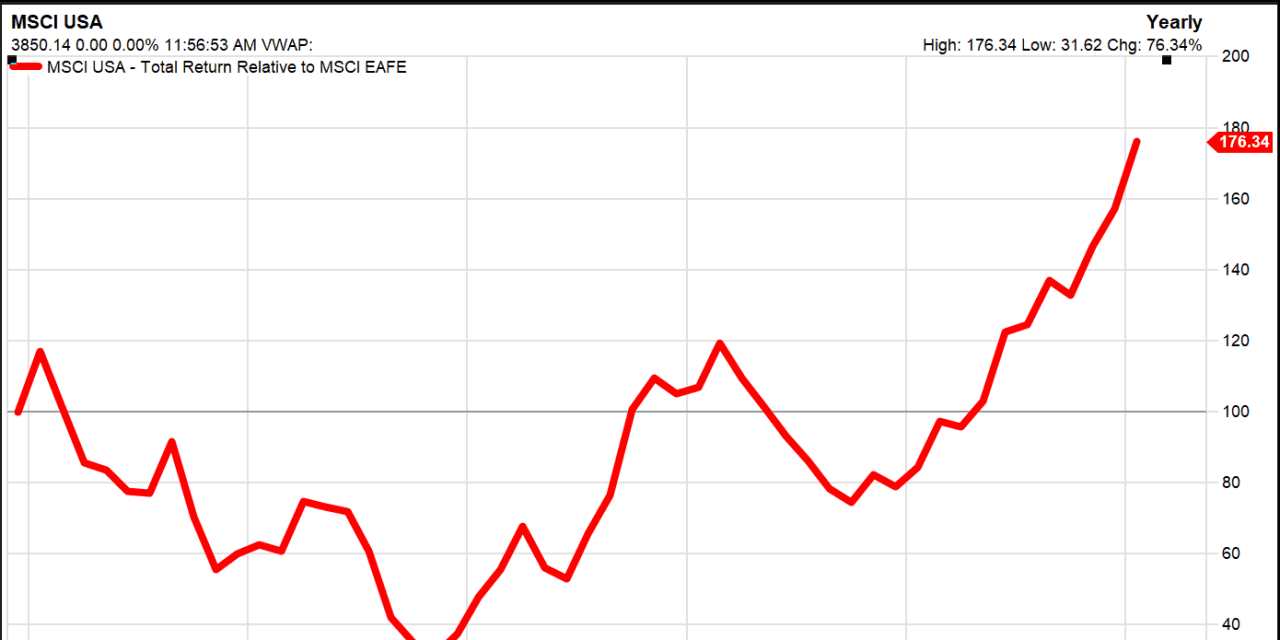

But we’ve been here before. U.S. stocks beat international stocks in the 1990s and in the decade just ended. But international stocks beat U.S. stocks in the 1970s, the 1980s, and the Zeros.

There’s a general tendency in finance — on Wall Street and Main Street—to treat U.S. stocks as ‘mainstream’ and foreign stocks as somehow risky and outré. That’s true even when you’re talking about stable, developed markets in Europe and Asia. It makes no logical sense.

The U.S. accounts for just 24% of global economic output, according to the International Monetary Fund, but nearly 60% of global stock market values (and 80% of U.S. investors’ stocks).

Personally, I wouldn’t have less than half my stock portfolio overseas — even if I thought U.S. stocks were cheap. And right now they are not cheap. I wonder what Jack would say?